In a study done by the Center for Digital Thriving, around 51% of people ages 14-22 surveyed have admitted to using a form of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) at some point. Respondents said the tool increased their productivity, but exactly how true are these claims? To answer this question, examining the impact of AI on students and its use in the classroom is necessary.

Unlike a decade ago, teachers now explicitly state in their syllabi when AI can and cannot be used. Most students argue tools such as ChatGPT are both harmless and beneficial; instead of critically reading a text for a history assignment, ChatGPT can condense all that information into wording that is easier to understand. The worry for most educators is that this shortcut is at the expense of student learning.

Another major concern is privacy. AI lives on vast amounts of data. In an academic setting, this translates to academic records of students and their personal information. Who is regulating data privacy and security? As AI becomes more integrated into educational settings, the chances for data breaches increase, leading to confidential data being exposed and misused. An article from CU Boulder explained that there is currently no effective policy holding third-party vendors who obtain this information accountable.

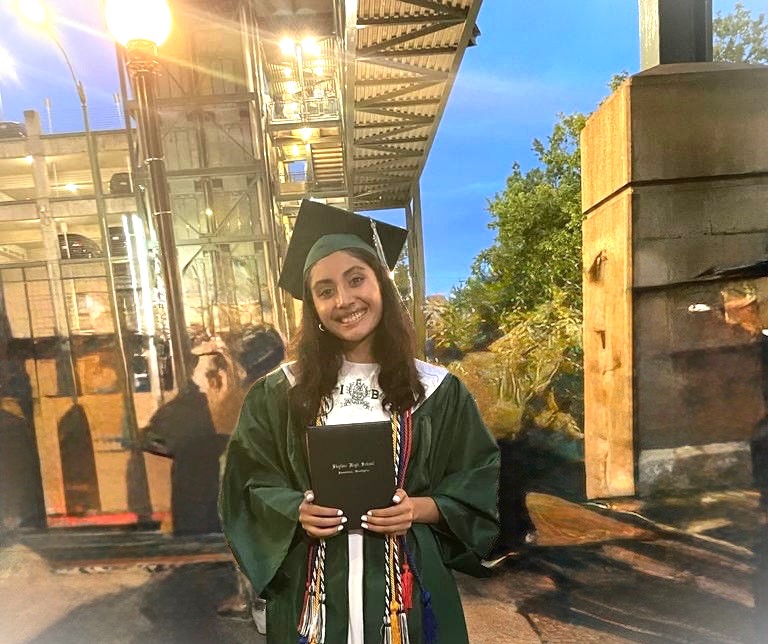

Teachers can also benefit from AI. The technology can grade student assignments, give feedback, and generate lesson plans. This automation may lessen the load for teachers but does not encourage proper student-teacher relationships. Skyline senior Nithya Shree Marimuthu reported “interacting with teachers helps me understand the topics more.”

Because AI operates on collected data and since this data is collected by humans, it may be filled with biases that fail to include a diverse array of people. These amplified biases extend to applications, interviews and admissions processes: one group of students is favored and set as the standard, while others are neglected.

Additionally, school districts predominantly serving students from low-income families may have limited access to AI-powered tech compared to their wealthier counterparts, widening the educational gap.

Arguably most important of all, excessive AI use in schools is an assault on a student’s ability to critically think. Alex Molnar, director of the National Educational Policy Center at CU Boulder, has called for an indefinite “pause” on the integration of AI into schools.

The example of critically reading a historical text, relying on ChatGPT seems like an ingenious alternative to working through the reading, but it establishes a pattern of dependence on AI. This dependence prohibits insightful analysis and a student’s want to approach learning from an empathetic point of view. If a flawed and biased AI system is constantly telling students how to interpret topics, pupils miss out on active problem solving.

AI is still a relatively new tool that needs a lot more regulation. If AI is to be implemented into education systems, its goal should be to support staff and students, not take away their creativity or restrict collaboration and in-depth learning. While AI was created to give computers the problem-solving and learning abilities humans have, an unchecked use of it can minimize the entire point of educating students.